I started coding when I was ten, not because I wanted to but because my father told me I could have FIFA 19 if I learned to code first. So I downloaded Grasshopper on his phone and started tapping through basic JavaScript exercises without knowing what a variable or a function was. I just wanted to play FIFA. That was 2017, and there was no ChatGPT, no Copilot, no Claude, no “vibe coding.” There was Stack Overflow, MDN docs, and a lot of copying things I didn’t understand until eventually I did.

I moved from Grasshopper to Lua because I wanted to make Roblox games, then Python because someone told me it was the real thing, then JavaScript and TypeScript because I wanted to make websites, then Rust because I wanted to understand what was happening underneath all of it. I’ve touched C, C++, and a little bit of Java along the way. Eight years of writing code across probably seven or eight languages, all before I turned eighteen. I say all of this not to flex but because it matters for what I’m about to talk about. I have a specific relationship with programming that most people writing about the future of code don’t have. I’m not a senior engineer at Google speculating about whether their job is safe, and I’m not a VC pattern-matching from pitch decks. I’m eighteen years old and I’ve been coding for nearly half my life, and the ground is shifting under something I have loved since childhood.

I was vibe coding before it had a name

I joined Cursor roughly 700 days ago, back in early March 2024. At the time, Cursor was a scrappy little startup that had raised an $8M seed round and had maybe 30,000 daily users. GPT-4 was still the best model available and Claude 3 Opus had literally just come out days earlier. There was no Claude 3.5 Sonnet, no GPT-4o, no o1, no reasoning models, and Cursor’s tab completions ran on what would now be considered ancient technology. Today that same company is worth $29.3 billion and has over a billion dollars in annual revenue.

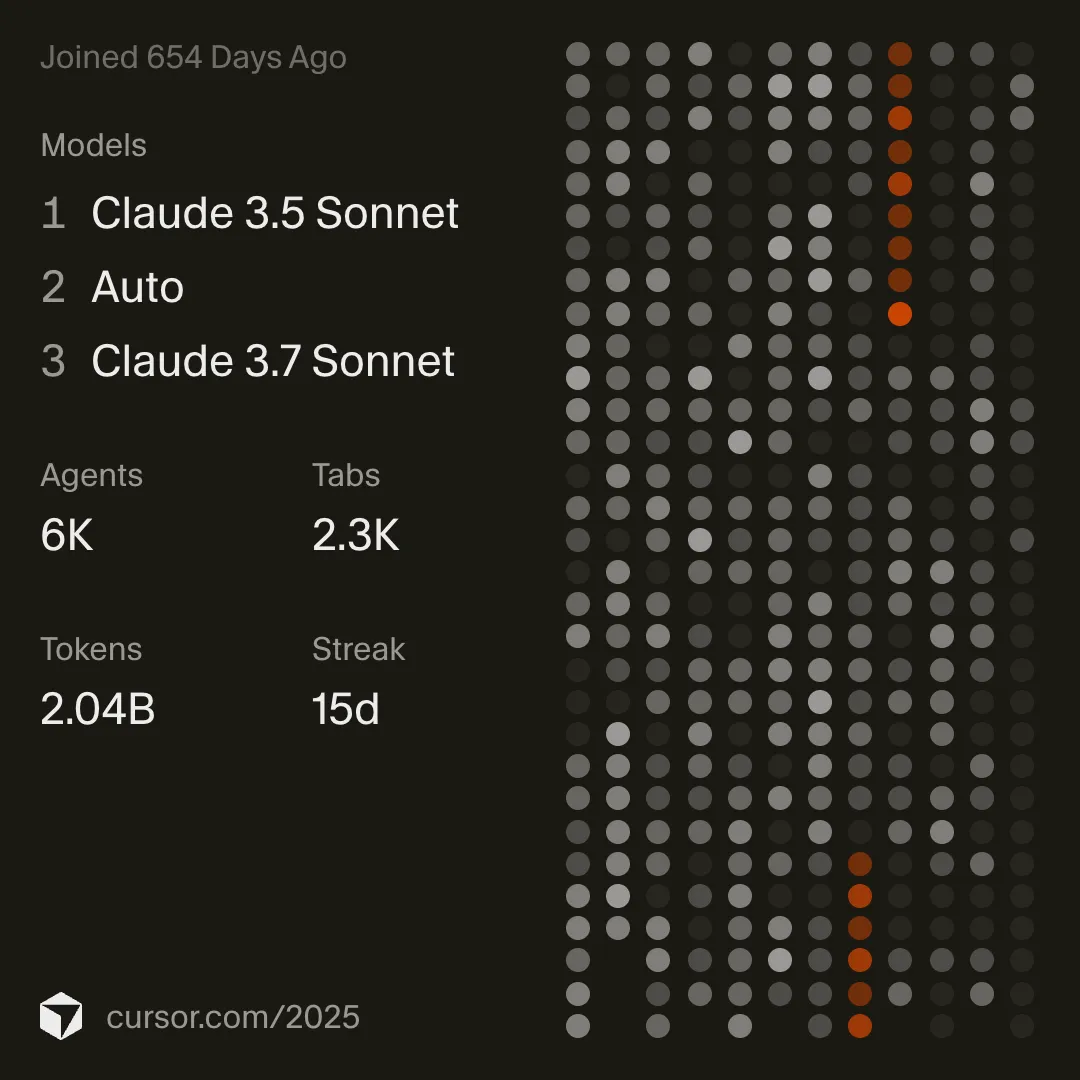

My Cursor year-end stats from December 2025. When I first opened this app, none of these models existed yet.

My Cursor year-end stats from December 2025. When I first opened this app, none of these models existed yet.

My OpenAI account is even older. I created it around April 2022, about seven months before ChatGPT launched on chat.openai.com that November. I was fifteen years old and messing around with GPT-3 in the OpenAI playground because I’d read somewhere that you could make it write code for you, which at the time felt like magic. When ChatGPT actually dropped on November 30th I already had an account and was one of the first people using it. As of today that’s almost four years ago.

My OpenAI account age as of October 2025, created months before ChatGPT even existed as a product.

My OpenAI account age as of October 2025, created months before ChatGPT even existed as a product.

My ChatGPT wrapped from December 2025 tells the rest of the story: top 0.1% of users by sign-up date, top 1% by messages sent, over 2,200 chats and 15,500 messages exchanged in 2025 alone, and obviously a lot more since then.

My “Year with ChatGPT” stats from December 2025. The 11.78K em-dashes was my biggest gripe about the tool.

My “Year with ChatGPT” stats from December 2025. The 11.78K em-dashes was my biggest gripe about the tool.

I bring these numbers up because the term “vibe coding” didn’t even exist until Andrej Karpathy tweeted about it in early 2025, and by the time the discourse started I’d been doing this for a year already. The experience of coding with AI isn’t theoretical for me. It’s just how I’ve been building for a long time now.

The problem with vibe coding tools

Let me be clear about something: I think tools like Bolt, v0, Lovable, and everything in that category produce pure slop. I don’t say that to be dismissive, I say it because I’ve seen what comes out the other end and it genuinely concerns me. These tools are fine for internal dashboards and throwaway prototypes. If you need a quick admin panel that only your team will ever touch, go for it. But the moment someone tries to use them to build a real product that handles real users and real data, things fall apart in ways that aren’t just ugly but actually dangerous.

I have a friend who vibe-coded a basketball tournament system where people could sign up, form teams, pay into prize pools, and compete for winnings. Sounds cool. The problem is he built the whole thing without understanding any of what was happening under the hood. I spent maybe five minutes poking around and found his Supabase credentials exposed in the client-side code. He had zero Row Level Security policies set up, none at all, which meant I was able to query his entire database directly and pull every user who had signed up along with their payment information and personal details. All of it sitting there completely unprotected because the AI that generated his code didn’t think about security and he didn’t know enough to check.

This is the reality of non-programmers building production software with AI. The code compiles, the UI looks… awful, and the demo is impressive, but underneath it’s a house built on sand and nobody notices until something actually goes wrong. My friend’s basketball app is a small-scale example, but imagine the same negligence applied to a fintech product or a healthcare system.

AI is brilliant if you actually know what you’re doing

Here’s where my opinion gets more nuanced, because I don’t think AI-assisted coding is bad. I think it’s the single biggest productivity gain in the history of programming, and I rarely write code by hand anymore. The only times I do are when I’m practicing for fun because programming really is a beautiful thing to do with your hands, or when I’m sitting exams at school where they still make us write code on paper like it’s 1995.

For everything else I use AI constantly, but the key difference is that I understand what the AI is generating. When Claude writes a React component for me I can read it and know immediately if the state management is wrong, if the effect dependencies are off, if the error handling is lazy. When it scaffolds a database schema I can tell if the relationships make sense, if the indexes are right, if the access patterns will actually work at scale. I’m not accepting code blindly, I’m reviewing it the way I’d review a pull request from a junior developer who’s fast but sometimes careless. This is the part that gets lost in all the noise about AI replacing programmers: the AI is the tool, and the programmer is still the one who knows whether the output is correct, secure, maintainable, and appropriate for the problem. Remove the programmer from that equation and you get my friend’s basketball app with exposed credentials and no security policies.

What stays important

I’ve been thinking about this a lot, and after eight years of writing code and almost two years of writing code with AI, here’s what I think actually matters going forward.

Understanding systems is more important than ever, and I don’t mean syntax or memorizing APIs but understanding how things actually work. Why does this database query take three seconds? What happens when two users hit this endpoint at the same time? Where does the data actually live? AI can generate code but it can’t debug a production outage at 2am when the error is three layers of abstraction deep and the logs don’t make sense. That kind of problem-solving comes from understanding the system, not from prompting.

Taste matters more than speed. Anyone can generate a thousand lines of code in ten minutes now, and the hard part is knowing which thousand lines to write in the first place. Architecture decisions, API design, data modeling, these things require judgment that comes from experience and from having built things that broke and understanding why they broke.

Security and infrastructure knowledge are becoming critical differentiators. The more code AI generates the more surface area there is for vulnerabilities, and someone needs to know what RLS is. Someone needs to think about authentication flows and token expiration and input validation. The AI won’t remind you.

What worries me

The thing that keeps me up at night is not that AI will replace good programmers, because I don’t think it will, at least not for a long time. What worries me is the gap it creates between people who look like they can build software and people who actually can. When the output looks the same on the surface, when the demo is polished and the landing page is clean, it becomes really hard to tell the difference between a solid product and a ticking time bomb.

And I worry about what this means for people learning to code right now, in 2026, who will never experience what it’s like to debug something for four hours with nothing but print statements and Stack Overflow. That struggle is where the understanding comes from. I’m grateful I went through it before AI made it optional, because it gave me the foundation that makes AI useful to me now rather than dangerous.

So where is this all going?

I think we end up in a world where programming becomes more about intent and less about syntax, where the best programmers are the ones who can clearly articulate what they want, understand deeply whether what they got back is correct, and know how to architect systems that are robust even when individual components are generated by machines.

The ceiling for what a single programmer can build is going to be absurdly high, and I already feel this. Projects that would have taken me months now take weeks, and the leverage is real and only going to increase as models get better and tooling improves. But the floor is going to drop too. More software will be built by more people with less understanding of what they’re actually shipping, and some of that will be fine but a lot of it won’t be.

If you’re learning to code right now, my advice is simple: learn the fundamentals before you learn the shortcuts. Understand what a database is doing before you let AI write your queries, understand what HTTP actually is before you let AI build your API routes, and build something painful and manual and ugly at least once so that when AI generates the clean version for you, you understand what it’s doing and why.

I started with Grasshopper on my dad’s phone because I wanted FIFA. Eight years later I’m building multi-agent AI systems and running a development agency. The tools changed completely, multiple times over. The understanding I built by doing things the hard way is the only thing that stayed constant.